I commit to the Leica S007

One of the most difficult decisions a professional photographer has to make is the decision to commit to a whole new camera system.

Unlike an amateur photographer, the professional has to commit to buying into a camera that will be useful (and a money-maker) for many years, not the least because the equipment is going to be expensive, and the costs amortized over many years. The professional has to take the long view, building his cameras and lenses as needed. The last thing he thinks about is chasing marketing fads.

It was with this background in mind that I made the decision to make the Leica S007 the next camera for my professional shooting, for reasons I will address shortly. For well over 20 years I relied on a Contax 645 and their excellent Zeiss lenses and I never regretted that choice. The camera served me well, allowed me to make a good living, and still works just fine. But the Contax is an “orphaned”camera, no longer supported by a manufacturer that left the camera business altogether. Should one of its circuits or shutter fail, it may or may not be repairable. It was time to make that big decision, to find a replacement camera for professional use and for the long term; thus began my search.

An early morning photograph from Salem harbor looking East. Leica S007 with a 35mm Zeiss Distagon lens using the Contax-to-Leica adapter. I used a 3-stop graduated ND filter to even out the exposure between the foreground and background.

In the professional realm, there has been a bit of a “format war” between 35mm-size digital sensors of ever-increasing pixel counts, and removable digital backs for medium-format cameras. My Contax 645 and its Leaf Aptus digital back fell into the second category.

A couple of years ago, it seemed as if the high-end options in 35mm sensor cameras would negate the quality differential obtainable from a large-chip detachable sensor, resulting in the demise of the market for medium-format digital cameras. This has not turned out to be the case, and paraphrasing Mark Twain, reports of the death of medium format digital have been highly exaggerated. In fact, the market segment is now quite active and competitive, and for good reason.

At the upper reaches of quality are removable digital backs that attach to cameras whose “DNA” comes from the days of film photography, my Contax 645 being one example. Such digital backs can be moved over to studio cameras for product or architectural work, allowing for perspective swings and tilts. Outside of the studio, however, this approach still leaves you with a camera that looks and feels like a film camera.

I gave serious thought to transitioning to a 35mm full frame camera, but stopped short because I had grown to appreciate the technical advantages of large digital sensors and that indefinable “medium-format” look. Simply put, even with my dated equipment, when used within its “comfort zone”, the image quality was spectacular.

It must be that special image quality that has led to the resurgence of medium-format digital, and led me to consider the Leica S system even though I had never thought of that company as a “player” in that realm. They seemed to have gotten right a long-term solution for me, for a number of reasons.

First off would be the ability (via the adapter) to use all my existing Zeiss lenses that performed well on the Contax 645. This eases the financial burden of adding a whole new set of lenses while allowing me to transition to Leica “glass” over time—smart thinking on Leica’s part.

Second was the S camera itself. Without sounding like a fanboy for Leica, I have to say that the company has placed the camera in the sweet spot between 35mm DSLRs and traditionally styled medium format cameras. It looks and feels good in the hand, an elusive quality that makes a difference in professional shooting situations.

I spotted this painted lightpole at a local supermarket. Leica S007 with a Zeiss 120mm Apo Macro-Planar using the Contax-to-Leica adapter.

Third was a certain attention to details rather than an emphasis on marketing gimmicks. To cite one example, the USB connection at the camera end uses a rather expensive locking connector normally used on laboratory or medical equipment. Speaking as one who never trusted the flimsy Firewire connection on the Leaf Aptus, this was a welcome improvement.

I will finish with comment on optical vs. electronic viewfinders. Now that CMOS sensors are the norm, it is possible to pull the lens image off the sensor and direct it to an electronic screen. I have no quarrel with that trend and it certainly allows for smaller lenses and bodies. But to repeat what I said above, reports of the death of optical viewfinders are highly exaggerated. The view through the Leica S viewfinder is gorgeous, and a lot easier on my tired eyes than the various 35mm cameras in my cabinet.

A rare double rainbow at about 6PM in Sarasota, FL. Leica S007 with a 45mm Zeiss Distagon lens using the Contax-to-Leica adapter.

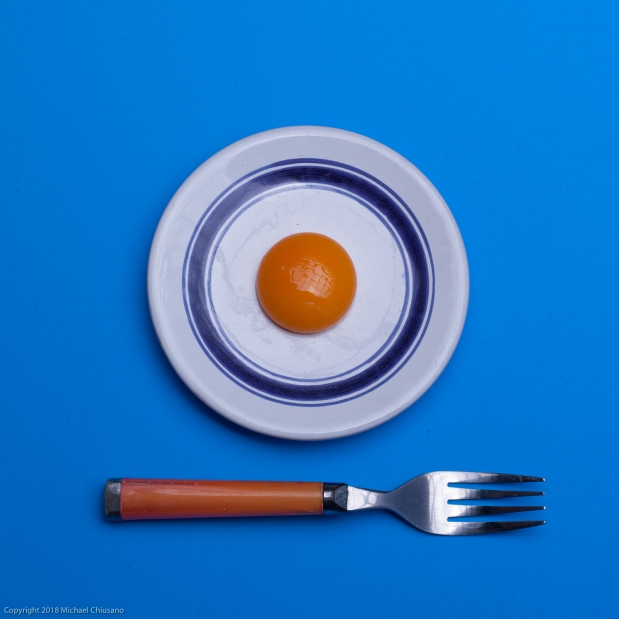

A running shoe store in downtown Sarasota. This is an interesting contrast of blue and orange colors, which are opposite on the color wheel. The square format of the Rollei was a perfect fit for the subject.

A running shoe store in downtown Sarasota. This is an interesting contrast of blue and orange colors, which are opposite on the color wheel. The square format of the Rollei was a perfect fit for the subject. We found this store selling shaved ice at a tourist part of Sarasota, FL. I had to brace my camera on a table and use a shutter of about 1/8 second to get an exposure. The colored lights are what make the shot.

We found this store selling shaved ice at a tourist part of Sarasota, FL. I had to brace my camera on a table and use a shutter of about 1/8 second to get an exposure. The colored lights are what make the shot. A rare double rainbow seen from the balcony of the house we rented. It was late afternoon, with the sun quite low in the sky. I had to use some Lightroom adjustments to darken the sky and bring out the rainbows.

A rare double rainbow seen from the balcony of the house we rented. It was late afternoon, with the sun quite low in the sky. I had to use some Lightroom adjustments to darken the sky and bring out the rainbows.